A Century-Old Adobe Schoolhouse Is Being Restored as a Community Hub in New Mexico

A small town in northern New Mexico is punching above its weight with a local historic preservation project.

Paid subscribers make my reporting possible. Consider joining them:

As a child, Jacobo Baca remembers being scolded for scrambling up the stone buttresses of his old parochial school in Peñasco — a small New Mexican town tucked into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, 50 miles northeast of Santa Fe. The supports seemed built for climbing, even if his teachers disagreed.

The historic Peñasco High School and St. Anthony Parochial School has long been an unofficial landmark along the scenic High Road to Taos. The single-story, 30-foot-by-180-foot rectangular adobe building — recently recognized on the National Register of Historic Places — has been empty and maintenance deferred since the late 1980s, when enrollment dwindled, and it ceased operating.

But the old schoolhouse will soon take on a new life as the Peñasco Valley Heritage Plaza.

“Our end goal isn’t just seeing the building restored,” says Jose López, executive director of the Peñasco Valley Historic Preservation Society (PVHPS), the nonprofit organization leading the restoration efforts. “We have a lot of programming that we are doing now and plan to further expand once we have the new space, centered around cultural preservation, economic development and community service.”

The new community center will host a museum, classroom space, a gift shop selling local wares, and a commercial kitchen with a pop-up restaurant. Outside, landscaped grounds will boast walking paths, a stage, and community garden plots. An outdoor seasonal farmers’ and crafters’ market has been running on-site since 2022, as a first peek at what’s to come.

The community center will serve not only the roughly 600 residents of the town of Peñasco, but the larger Peñasco Valley. The area’s majority-Hispanic, tight-knit and somewhat isolated population maintains generations-old traditions of farming, cooking, and herbal medicine. Some still speak a dialect of Spanish that López says borrows from Indigenous Puebloan and Nahuatl languages and features unique words for the region’s landscape and architecture.

“The culture is one of the things that’s really unique about northern New Mexico and especially these smaller villages up here, where distinct cultural aspects have been preserved,” he says.

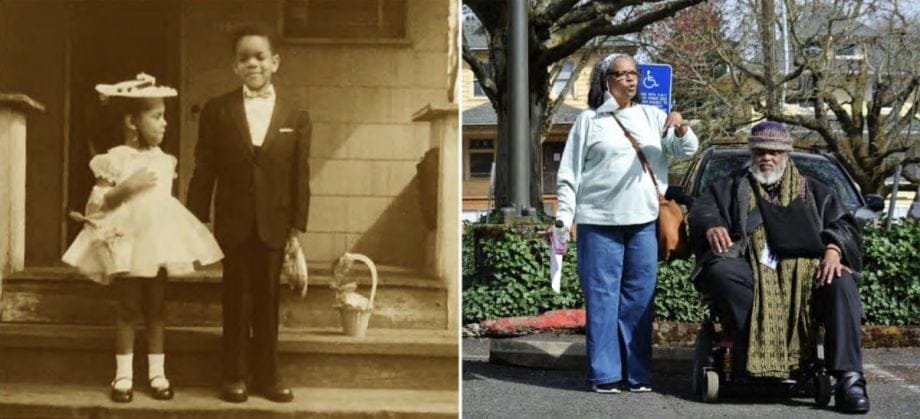

Saving Peñasco’s crumbling schoolhouse has been a labor of love for many in the area, as well as past students and residents who maintain strong ties to the community. “The building itself means a lot to people. It has a lot of memories, and we want to preserve those memories,” says Alfredo Romero, who attended St. Anthony when it was a parochial school in the 1950s. Romero now serves as PVHPS president.

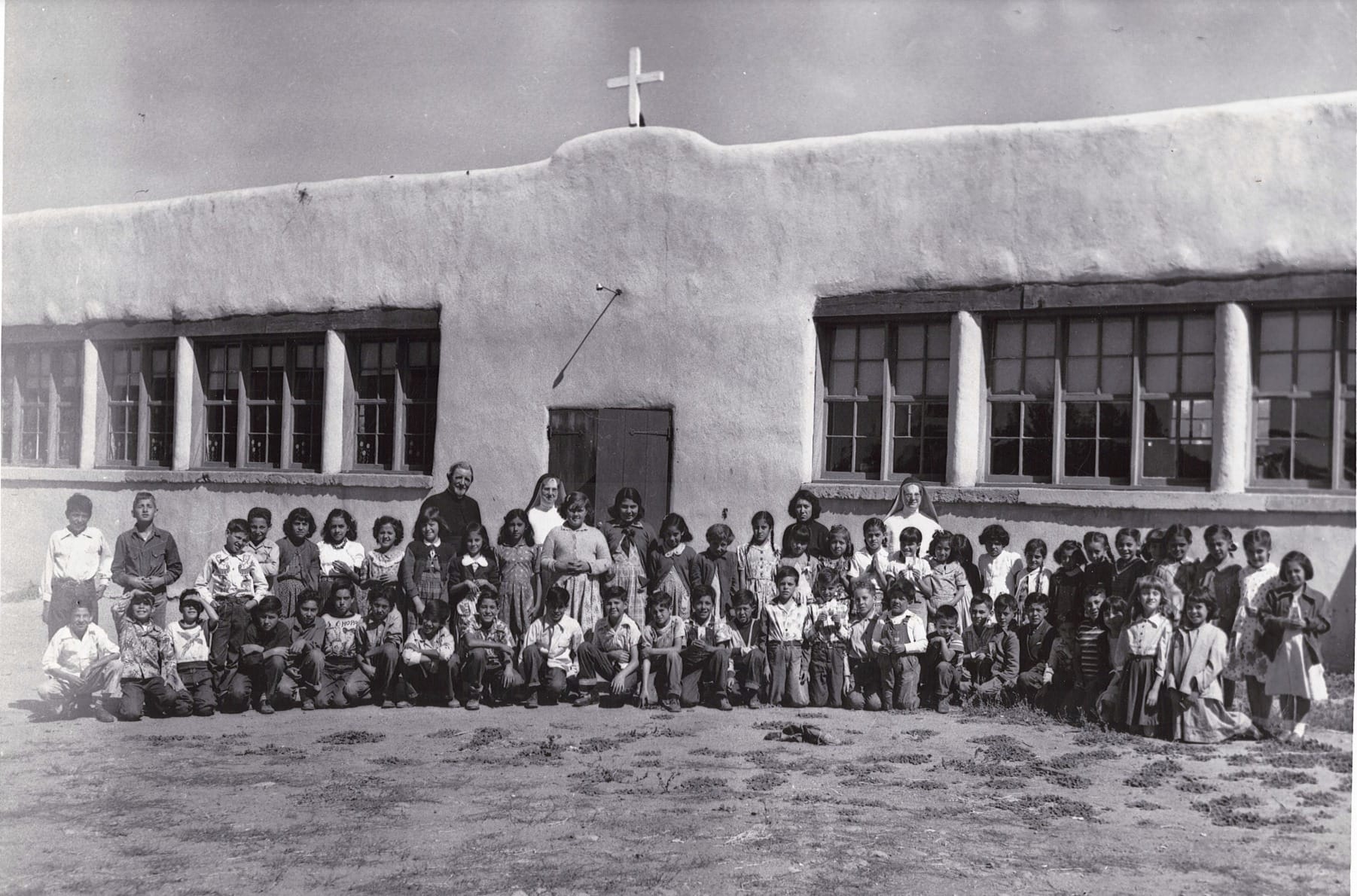

An earlier generation of students remembers the school as Peñasco High School, one of the first public schools in Peñasco Valley. The Archdiocese of Santa Fe founded the school, and local artisans were contracted to build it in 1931. What began as two classrooms was later extended in sections to house six classrooms separated by wooden accordion doors. Dominican Sisters from Grand Rapids, Michigan, moved to New Mexico to teach, and the Archdiocese leased the building to Taos County to operate the school.

L to R: Community members mudding the old Peñasco High School; A historic photo of Old Peñasco High School students with a priest and sisters; A crack in the southwestern corner of the building, near a window and the roof.

“That was how public education actually grew in these small villages for decades,” explains Baca, who grew up in Peñasco and is now a professor of Chicana and Chicano studies at the University of New Mexico.

Things changed about two decades later, as a now-famous lawsuit progressed through New Mexico courts. Known as the Dixon School Case, that suit reached the state Supreme Court and became the first state case to enforce the separation of church and state in public schools. The case was filed in 1947, and the New Mexico Supreme Court decision came down in 1951.

But in between, Baca says, “The state had just enough of a window, and there was a scramble to build school buildings [and] develop public schools.” Peñasco’s new public school opened in 1948, and the old school continued to operate as St. Anthony’s Parochial School for close to forty years.

After the school closed, the building was abandoned.

“It became an eyesore,” admits Romero. So, in the 1990s, he says, “A group of former students got together and said, ‘Let’s see what we can do.’”

Progress was slow and piecemeal. In 1997, the group engaged Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a Santa Fe-based organization that helps communities connect to contractors, technical support, funders, and other resources to preserve their historic structures. Together, they produced a conditions assessment showing what work was needed to save the old school building. Lacking support for major intervention, occasional community service events brought together locals to tackle small but vital repairs.

“The wonderful thing about Cornerstones, as well as [PVHPS], is that here in New Mexico, funds are usually not readily available, but we do our best when it comes to working with little funds or no funds, mainly putting people to work in community gatherings,” says Francisco Uviña-Contreras, a professor of architecture at the University of New Mexico and an expert in adobe preservation, who has consulted on the Peñasco project.

Uviña-Contreras says that adobe buildings lend themselves to this model.

“Your great-great-grandfathers or grandmothers built with it, and you can do it the same. It’s not a technology that’s only in the hands of professionals.”

A leap forward came in 2017 when community members formed PVHPS as part of an organized effort to prevent the demolition of the old school building.

Since then, the organization has secured grants from the New Mexico Department of Tourism, the New Mexico Community Trust, and the Catholic, Healy, and Kit Carson Electric foundations. It has also raised over $100,000 in private donations at bi-annual galas held in Peñasco and through online donations that trickle in from supporters, including many past students and Dominican Sisters across the country.

PVHPS purchased the old school building from the Archdiocese of Santa Fe for $30,000 in December 2021. Its grant from the Kit Carson Electric Foundation allowed it to purchase tents, tables, chairs and other supplies to launch a farmers’ market – its first on-site community program — in the summer of 2022. The market caters to small and first-time vendors.

“We have so many people here whose families have been growing in the valley for generations, but at the same time, Peñasco is a food desert,” explains López. “The formation of the farmers’ market kind of tackles that problem.”

Work on the building began later, after firms were hired to conduct a new assessment report and draw up construction documents. Currently, stabilization work is underway, and new grading and drainage work is expected to begin this spring. Restoration and construction work within the building will follow and is dependent on further funding. The total cost of the preservation project is estimated to be over $1.5 million. PVHPS has set a goal of completing the entire project by 2028.

López hopes that the school’s place on the National Register of Historic Places will help secure the additional funding needed to complete the effort. The site earned that recognition in 2023, thanks to its connection to the Dixon School Case and its unique architecture.

The listing comes with additional responsibilities to retain and preserve character-defining features from the building’s era of significance. At the school, those features include its divided lite windows, interior panel doors and classroom partitions, wooden flooring, viga and plank ceilings, and exterior stone buttresses supporting its long walls – the same buttresses Baca climbed when attending religious education classes after school at St. Anthony’s.

Every generation has its stories like that: For Romero, memories of heated basketball games played on an old court outside still put a smile on his face. Although the school had been closed for years by the time López was born, he recalls joining a community service day when he was around 10 years old, mudding the exterior walls.

López says he looks forward to new generations having their turn to make memories in the old schoolhouse: “This is an important way we’re serving our community.”

This story was originally published by Next City, a nonprofit newsroom reporting on solutions for equitable and just cities. Get Next City’s stories in your inbox: nextcity.org/newsletter.