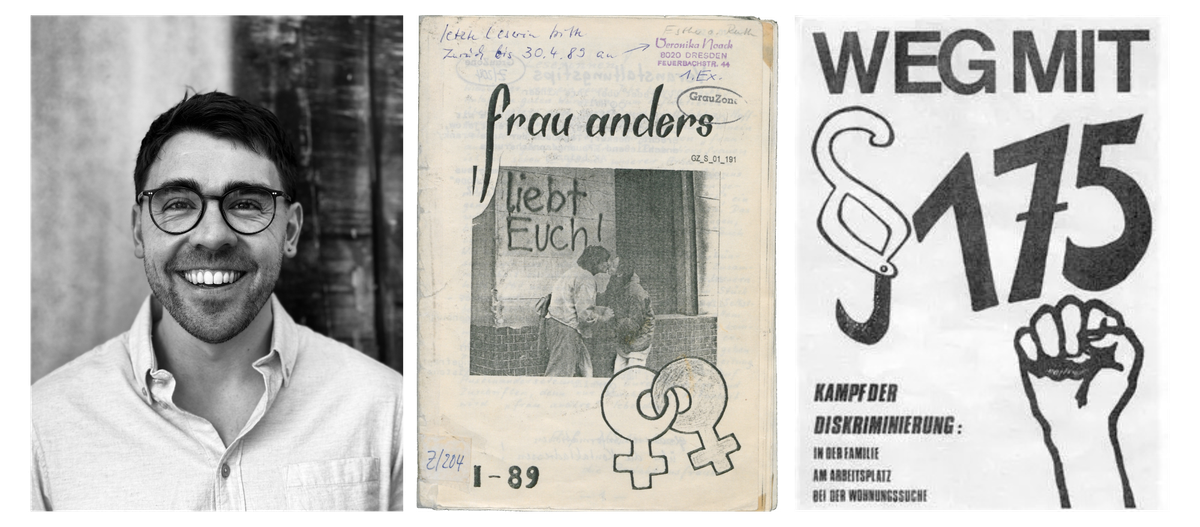

Josh Armstrong on LGBTQ+ Life in East Germany

Historian Josh Armstrong discusses the origins of a gay movement in East Germany and how its members thought about socialism.

Paid subscribers make my reporting possible. Consider joining them:

Historian Josh Armstrong studies queer life in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, also known as East Germany). I spoke to him earlier this year while writing a profile of Queer Voices for the summer issue of the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Queer Voices is a series of audio walking tours that explore LGBTQ+ histories in Leipzig and Halle, two former East German cities. I joined a tour in Leipzig last summer and was guided through parks, squares, and past the New Town Hall (located around the corner from a historical cruising zone, apparently), listening to oral histories transmitted through a glowing headset. One of my favorite interviewees was Elke, who spoke about life as a lesbian in East Germany and how she met her first great love, Nanni, at a house party in 1975.

After Germany was divided following WWII, the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany, also known as West Germany, took different approaches to legislating LGBTQ+ life. One of the most obvious differences was that East Germany reverted to the pre-Nazi era version of Paragraph 175, a nineteenth-century law that criminalized consenting sex between men. It all but stopped prosecuting gay men under the law in the 1950s and struck any mention of same-sex relations from its penal code in 1989. Meanwhile, West Germany retained the stricter Nazi-era version of Paragraph 175 until 1969, and only decriminalized same-sex relations in 1994.

“From a limited, legal perspective, it was better to be a gay man in East Germany than in West Germany,” says Armstrong. “But there was no infrastructure and no community, so in other ways, it was not as advantageous.”

In this week’s newsletter, Armstrong and I discuss contradictions like this one, which challenged his thinking during his research. We also discuss the origins of a gay movement in East Germany, how East and West Germany influenced one another on LGBTQ+ issues, and the spaces of queer joy and mutual aid that sustained LGBTQ+ communities under authoritarian rule.

Editor’s note: These responses have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Marianne Dhenin: What was life like for LGBTQ+ people in the GDR?

Josh Armstrong: You can sum up the situation as one of perhaps less overt homophobia than in the West, but far less infrastructure and fewer opportunities. You had to gain permission from the state to gather in a group, so you couldn’t just launch a gay knitting club and expect people to turn up. You had to get permission for that, and permission was usually not granted.

There are a couple of examples of magazines, queer magazines, that circulated. Particularly, there's a lesbian magazine called “Frau Anders” that suggests a kind of quite distinct loneliness and people yearning for community but not having it. Some of the literary works I read tell the story of people thinking they’re the only one who feels this way. There’s nothing about it in school. There are no role models. There’s nothing about it on TV or the radio. The vast majority of the literature that does exist, the literary fiction, was published in the late 1970s or early ‘80s. In the 1950s and ‘60s, there was basically nothing that came from the GDR, and there was very little that came from the West either. So, there wasn’t necessarily a queer community to speak of for many, many years.

That community was later established in big cities, such as Berlin, in the 1970s and ‘80s, but before that, there was significantly less. As with any dictatorship or oppressive society, you saw pockets of freedom and emancipation, but there was a lot less infrastructure.

MD: Could you share an example of one of those pockets of freedom that emerged in the early GDR?

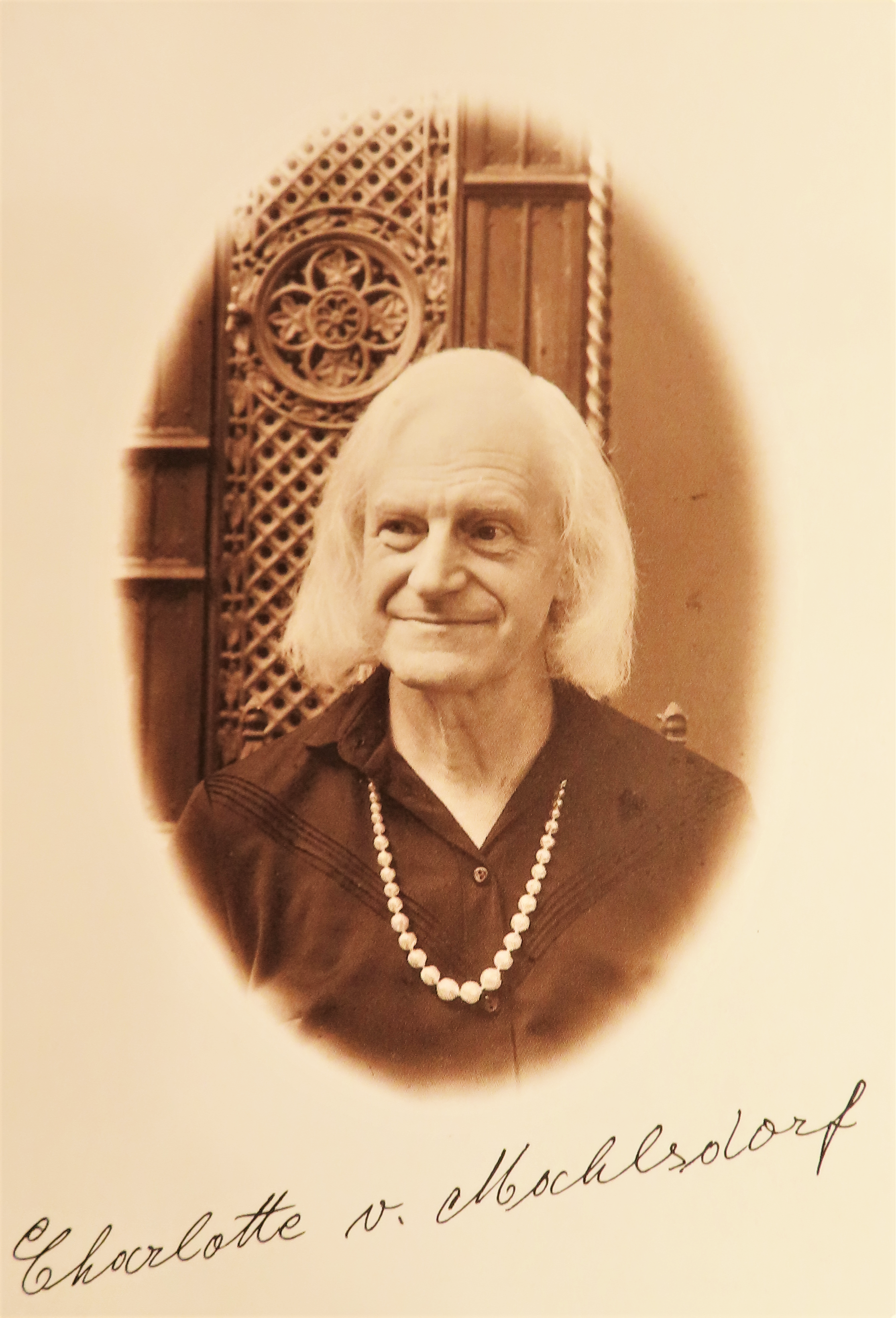

JA: One illustrative example might be Charlotte von Mahlsdorf. She was the most prominent trans woman in East Germany. She was this fabulously camp, German Hausfrau, and she inherited a big house in an eastern suburb of Berlin, called Mahlsdorf. She used it to host gay meetings and parties because those couldn’t be hosted elsewhere. She even illegally rented the space to the queer community until a police raid in the late 1970s. After that, the whole thing got shut down because it was just too dangerous.

Clockwise from top left: Charlotte von Mahlsorf guiding visitors through Gusthaus Mahlsdorf in 1977, image from the German Federal Archive; Charlotte von Mahlsdorf with children visiting Gusthaus Mahlsdorf in 1977, image from the German Federal Archive; Sepia-tone portrait and signature of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf; Gusthaus Mahlsdorf/Gründerzeitmuseum photographed in 2013.

MD: You mentioned that LGBTQ+ communities formed in cities in the 1970s and ‘80s. What started that movement?

JA: The first gay movement, and it really was a gay movement rather than a queer movement, was sparked when a group of men watched this movie, called “It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives” (Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt) in an East Berlin apartment.

That inspired one of the earliest organizations, called the Homosexual Interest Group Berlin (Homosexuelle Interessengemeinschaft Berlin, HIB). It was active throughout the 1970s and had various campaigns, activities, parties, and community events, and it tried to change the legal situation, as well. It disbanded in 1980 after a failed attempt to lobby the state to establish a queer community center..

Then, the Protestant Church played an important role in a second wave of activism in the 1980s because it was one of the only organizations that wasn't completely under state control. It offered rooms for people to meet, as well as photocopiers and paper for printing and distributing magazines, articles, and communications — that’s really how the activism got going.

There was also the Sonntagsclub, for example, in Berlin, which was founded specifically outside the church, as many people saw the contradictions and didn’t want to be part of the church.

MD: These groups had such limited space within which to organize and press for change. What did they manage to achieve?

JA: The more the activism got going, the more the state noticed it. By the end of the 1980s, you actually see an extraordinary change in the state’s attitude and concessions to the queer community.

The biggest one was a legal change that came into force in 1989, when Paragraph 151, which succeeded Paragraph 175 and was meant to protect minors from same-sex predation, was scrapped from the books, so there was no longer any mention of homosexuality whatsoever in the GDR’s legal code. That happened in East Germany before it did in West Germany, which only made the change in 1994.

MD: What was the relationship like between East Germany and West Germany on LGBTQ+ issues?

JA: The GDR and the Federal Republic, in their 40 years of coexistence, are both characterized by profound insecurity vis-à-vis each other. It's this competition of trying to be the best always, and one way of reading it would be that the tide had turned so much by the late 1960s that actually decriminalizing homosexuality would make one the better state. And the GDR was first, and then the West followed suit very quickly afterwards. I mean that's a very sympathetic reading of this, but I'm sure it had something to do with the fact that it happened almost instantaneously, one year after the other.

It’s also interesting that, after the wall fell in 1989, you had this odd legal situation where, in Berlin, certain relationships were legal on one side of the street and illegal on the other, because you still had the different legal structures.

MD: What did the East German LGBTQ+ movement think about socialism?

JA: One of the things that really comes out of, especially the literary works that I analyzed, was a kind of deep satisfaction with socialism, both the idea of socialism and the lived experience of socialism. I did not find this anarchist “We want to burn down the system because we don't belong here” attitude; rather, I found a “We want to widen the goalposts, such that we can apply for a flat together and maybe open a shared bank account” attitude.

I struggle with that a little bit because it comes from an assumption that queer people might think one way. Maybe that assumption [about queer people] is based exactly in this kind of Western thinking of “Burn the system down.” But that’s just not what they wanted to do. Rather, there’s a sense of satisfaction or contentment that comes out of these texts, even though they were denied really basic things that we might take for granted, and that were won with the political changes that came later.

For more on LGBTQ+ life in East Germany, Armstrong suggests:

- “Homosexuality Under Socialism in the German Democratic Republic” by Josh Armstrong in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics

- “I Will Survive: Der Kampf gegen die AIDS-Krise,” a German-language podcast about the AIDS Crisis in Germany from Bayerischer Rundfunk

- “States of Liberation: Gay Men between Dictatorship and Democracy in Cold War Germany” by Samuel Clowes Huneke

- “Ich bin meine eigene Frau” (I Am My Own Woman), a German-language semi-documentary about the life of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf from director Rosa von Praunheim

- “Queer Lives Across the Wall: Desire and Danger in Divided Berlin, 1945–1970” by Andrea Rottmann

- “Uferfrauen: Lesbian Life and Love in the GDR,” a documentary from director Barbara Wallbraun