Agrimovement on Farmworker-Led Organizing for Food Sovereignty in Lebanon

In a nation where one in five is starving, a powerful farmworker solidarity movement has emerged.

Paid subscribers make my reporting possible. Consider joining them:

Lebanon has been weathering a major food crisis for years. Already facing an unprecedented economic meltdown and nationwide protests beginning in 2019, conditions worsened in August 2020 when massive explosions at the Port of Beirut destroyed the nation’s grain silo infrastructure and the main entry point for essential food imports. Today, 21 percent of those living in Lebanon struggle with hunger.

But the crisis has deeper roots. Because Lebanon shares its southern border with historic Palestine, the Mediterranean nation’s trajectory has been significantly influenced by Zionists since the early twentieth century in the lead-up to the Nakba, when Israel expelled at least 750,000 Palestinians from their homes and declared statehood in 1948.

“Members of my family on my mother’s side were expelled from villages on the border in 1948, since the Nakba,” explains Bashar Abu Saifan, whose family comes from Bint Jbeil and surrounding areas, where several villages were ethnically cleansed in 1948. “Those villages have been facing, until now, one hundred years of border clashes and the Zionist expansionist mindset.”

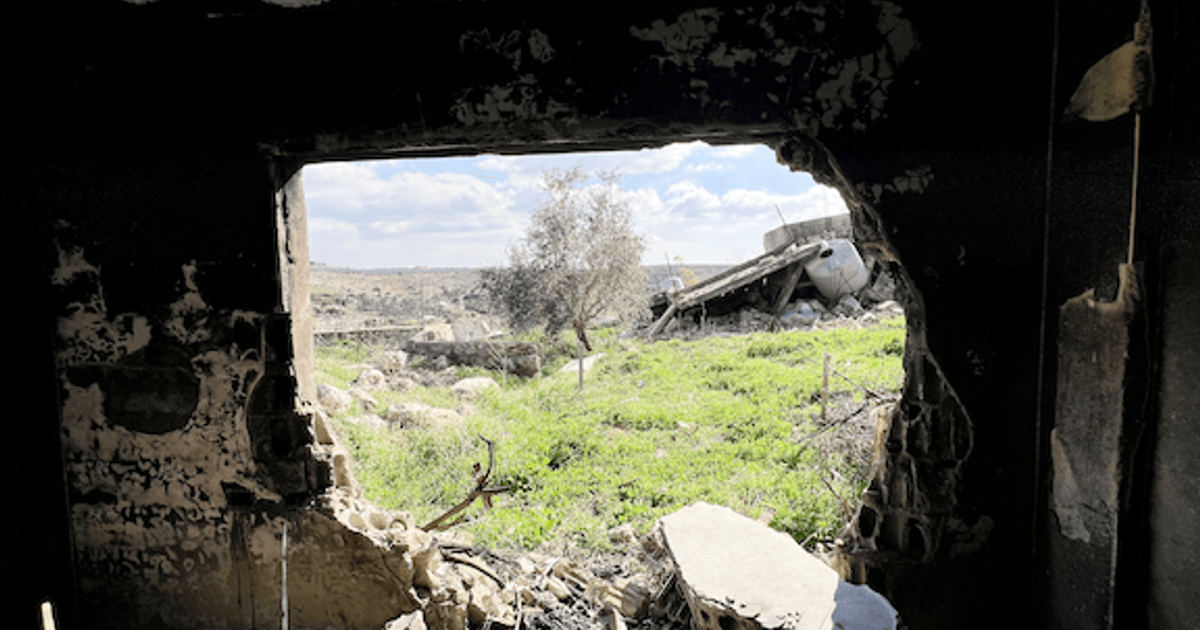

Those villages are also home to many of Lebanon’s smallholders and fertile farmland. Historically, farms in the south and the Bekaa region, nestled between mountains in Syria and Lebanon, account for over 60 percent of the nation’s agricultural production. Now, Israel has destroyed thousands of acres, and farmers have been forced to abandon tens of thousands more under threat.

“The fields are still there; people could grow their crops, but they are banned from entering by drones,” said Abu Saifan. “It’s like these are occupied villages.”

Abu Saifan is the co-founder of Agrimovement, an organization launched in Beirut in 2019 to work toward justice for workers, their families, consumers, and the land in Lebanon’s food system. For this week’s newsletter, I spoke to him and Sara Salloum, the organization’s president. We covered how foreign companies and genetically modified seeds and pesticides have remade Lebanon’s food system, how Israeli forces have remade the land, and how grassroots organizing could help roll back these changes and foster a more just and sustainable future.

Landscapes in Lebanon's agricultural regions L to R: Southern Lebanon from Rashid Kreiss via Unsplash; Marjaayoun in southern Lebanon from Ahmad Bader via Unsplash; Kfar Danis in Beqaa from Ibrahim Zada via Unsplash.

Marianne Dhenin: Agrimovement is meant to be a movement more than an organization. What does that mean about how you approach your work?

Bashar Abu Saifan: Agrimovement formed due to the need for a safety net for smallholder farmers and for everybody working in the food system, so the work that we do is broad, but all fits under the theme of justice in the food system. Agrimovement started by working with smallholder farmers, developing small service centers with them that provide farming inputs and training in ecological farming practices. This aspect runs parallel to our political action work, where we work with parliamentary members on policies related to GMO seeds and the preservation of biodiversity in Lebanon. Working with Syrian women refugee farmers to advance their rights and those of their children is another priority for us, and we have a study on [their working conditions and abuses they face] being published soon.

MD: Lebanon has been grappling with food shortages for years. What are some of the issues that have contributed to that crisis?

Sara Salloum: We believe that food has become a weapon in Lebanon. We don’t have wheat because the silos were destroyed during the port blast. Now, during the war, in the south and Bekaa, the areas where we have the most agriculture, farmers have been forced to stop producing.

We also have a problem with F1 [genetically modified, hybrid] seeds and the loss of heirloom seeds, which have a lot of nutritional value, support biodiversity, and are resistant to climate change. Currently, Agrimovement is advocating against a highly concerning proposed seeds law that puts Lebanon’s millennia-old agricultural heritage under imminent threat due to pressures from global markets and Western interests. The draft law was pushed forward without any involvement of local actors, especially farmers’ groups, unions, or civil society organizations.

The proposed framework is engineered in a way that will systematically marginalize small farmers, who are the backbone of our agriculture, by favoring industrial seeds and creating a cycle of dependency, debt, and seed monopolies. It introduces heavy financial and bureaucratic burdens, like complex licensing, registration requirements, and inspection fees, that small producers cannot meet, ensuring that only large, well-capitalized entities can control the seed market.

Already, a huge number of companies and stakeholders promote F1 seeds, like avocado seeds. Avocados need a lot of water and chemicals to grow, and we don’t have enough water in Lebanon. We have a water shortage.

Abu Saifan: Banana is another example. The rains here are strong enough to damage banana leaves, so farmers cover them; they put more money into covering the plants with a special fabric. If you do the math, everything on some of these farms is imported, and everything will be exported, so it benefits foreign investors, not Lebanon’s economy.

MD: What initiatives do you have to help preserve and increase planting of native seeds?

Abu Saifan: We believe in food sovereignty, ecological farming, the living seed bank, and [achieving this through] a grassroots movement, so that’s why Agrimovement is building programs with farmers. A few years ago, we launched our first small seed exchange program for farmers — without money, they bartered their seeds to support each other. We also grow special heirloom seeds with farmers in southern Lebanon, eastern Lebanon, and the Bekaa Valley.

We also have programs to provide municipalities with the right expertise to build ecological and permaculture farms as a model. We built one with the union of municipalities in Tyre, the biggest agrarian city in southern Lebanon, and we're replicating that with five more municipalities in southern Lebanon. These will become service centers for farmers; they have plant and sapling nurseries, and the farmers work in them and distribute the produce amongst themselves. They are also linked to the National Seed Bank for scientific identification.

Salloum: Specifically for farmers, we want to offer alternatives and alert them about the big companies harming our food system, starting with Bayer and Syngenta. We give farmers heirloom seeds so they don’t have to rely on those companies, we advocate for their rights in government, and we introduce them to ecological farming practices, like how to rehabilitate soil and have their own compost.

MD: What has changed since Israel’s invasion of Gaza and intensified attacks on Lebanon? How has Agrimovement responded?

Abu Saifan: It’s important to say that it isn’t a conflict; it’s a colonial action, and the catastrophe is huge. We’re talking about Gaza-like things. There’s nothing standing in some of these villages. Even the wells, the springs, and the infrastructure — they razed 35 villages to the ground. Some experts call this geocide; geocide is changing the landscape. Wherever you have springs, water, and plains, they’ve turned upside down the hills, everything. Elsewhere, the drones chase and hunt farmers; they're banned from entering these villages. This has happened in several villages in southern Lebanon.

One way we address this is through a solidarity action between farmers: A group of farmers propagates several types of fruit trees and gives them to the farmers in the south who are returning to their land. Along with our partners in the Arab Network for Food Sovereignty and the Arab Group for the Protection of Nature, we have distributed 16,000 saplings so far, and in December, we will distribute another 10,000 olive trees in cooperation with the municipalities.

Really, the clashes between Lebanon and the Zionists go back to the 1930s and 40s. That’s why we say that resistance in Lebanon is an organic thing passed from father to son to grandson — resistance, with its broad meaning, containing first solidarity, and also resilience, steadfastness, and patience.

For more on geocide and food sovereignty in Lebanon, Abu Saifan and Salloum suggest: